My father was an active man throughout his life. Born in 1912, his formative years were effectively bookend between two world wars – not the easiest of times. The baby of the family by some way, and with a brother, Eric, who had been a young (very) midshipman at Gallipoli and went on to command battle cruisers in WW2, and another brother, Laurie, who was an outstanding mathematician, all combined with a rather wayward and absent father, I get the feeling that Dad was a bit lost. He found himself through walking in the countryside around Tunbridge Wells and climbing on the many sandstone outcrops to be found there.

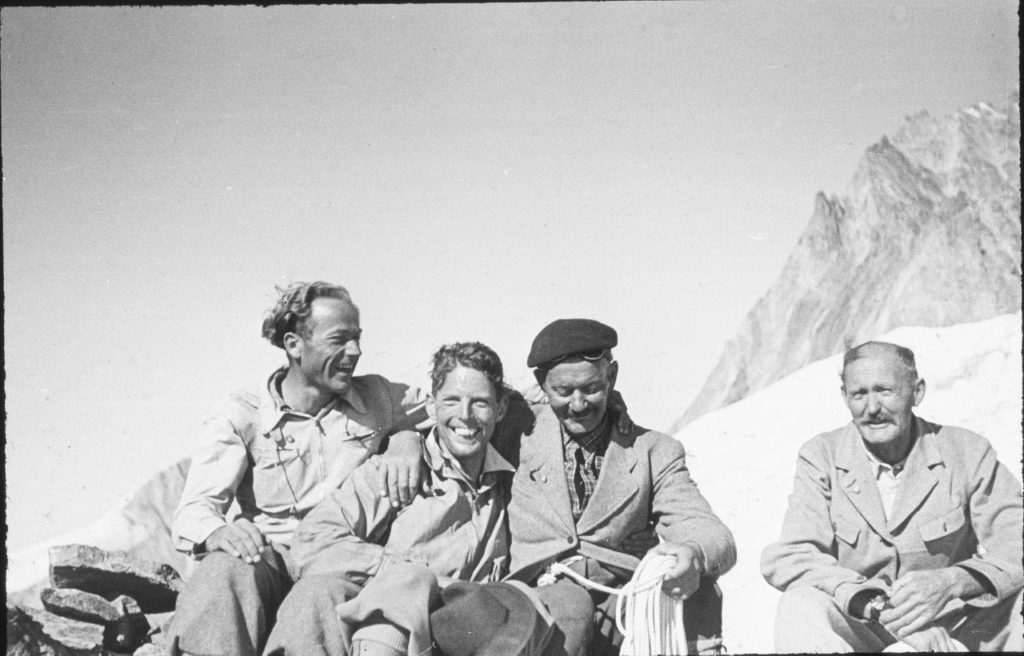

Although money was clearly tight, he always managed to save enough to go climbing in the Alps – at a time when Switzerland was still relatively cheap if you had sterling and were prepared to travel rough. Looking at the pictures, you can see such a happy young man, clearly building strong and lasting friendships – not only with the friends he went with, but with the older guides, who appear to have become surrogate fathers. (Col Durand, Zermatt)

Post-war he kept up his walking, now with a number of beloved Red Setters, and his climbing started to extend to North Wales with the Climbers Club and continued to return to Switzerland, meeting up with friends in the Swiss Alpine Club – where he was a member too. In fact one of his Swiss friends became my godfather – and you could not find someone who was further from the reserved stereotypical Swiss: he was open, loving, generous and with a huge sense of humour.

Clearly this was a fun life for a single man and perhaps because of that, and the dysfunctional family life he had experienced, my father married late. And although the Alpine expeditions stopped when my older brother and I came on the scene, the walking and climbing on the sandstone rocks continued. For us children, our first tentative steps were on the soft sandy paths, first scrambles and tumbles on the easy sloping slabs, and then longer expeditions onto Ashdown Forest and attempts at ever more technical climbs.

The arrival of much-loved Labradors just made the whole walking experience more fun. In fact, walking was so part of our life and it never struck me that others did not spend so much time outdoors in all weathers.

We also did longer walks while on our regular holidays in the Spey Valley in Scotland: ‘Four Caingorms in a day’, the Lairig Ghru and the Lairig an Laoigh were all great favourites. Nights out under the Shelter Stone at the top end of Loch Avon (pronounced A’an) or tramping in to fly-fish for lightning-fast little trout on the moraine lochs in Glen Einich are still magical memories I treasure.

Sometimes we would go back to Switzerland to visit my godfather and revisit the areas my father and he had explored when they were young. I well remember being introduced to an aged guide in Grindelwald, one who had undertaken some great climbs with my father on the Monch and the Jungfrau. My father and he embrace on meeting and the warmth of their interaction as they recalled their times together was striking – and starkly contrasting to the single cold meeting I had had with his father – my grandfather.

Dad remained fit and healthy into his older age and at 75 we even did the Lairig an Laoigh pass – 29km through the Cairngorm Mountains. At 6’ 4’’ and 13.5 stone, tanned and with a full head of hair he hardly looked his age, though I was acutely aware that Mountain Rescue would be unimpressed should anything have gone wrong on such a remote route. Luckily nothing did happen and what a magnificent day it was and such a wonderful shared experience to look back on, right to the end of his days.

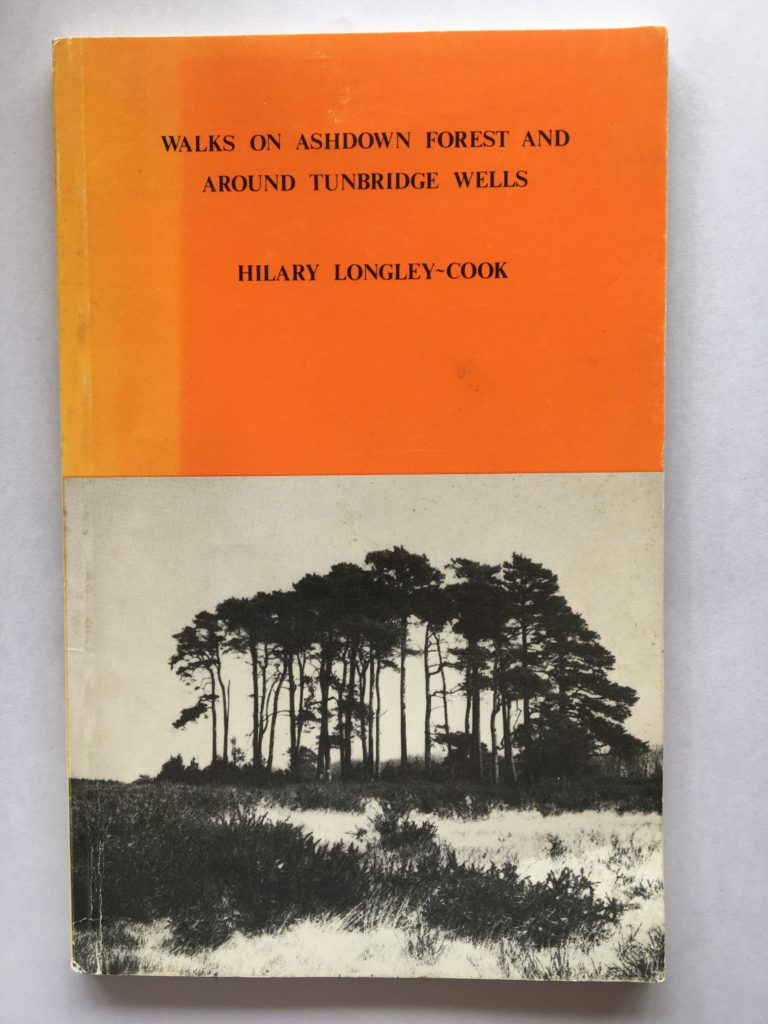

When my father had retired Mum wanted to get him out of the house so, knowing his passion for walking and sharing his routes, she suggested he write a walks guide. He set about this with a real focus and a year or so later published a book of 25 ‘Walks on Ashdown Forest and Around Tunbridge Wells’ which encapsulated the wonderful walks we had all done growing up. He had it bound the size of an OS map and in bright orange, supposedly so he could see if anyone was using it – though whether to give support or avoid those people who had it he never made clear!

Published first in 1973 it went through four reprints before 1985 and finally, he passed on the copyright to the Conservators of Ashdown Forest.

Here’s hoping people get as much from this blog as others got from Dad’s book.